[This article was first published in Catalonia Today magazine, Dec. 2022 under the title “Promenade of multitudes”]

A really good book is a universe away from its marketing.

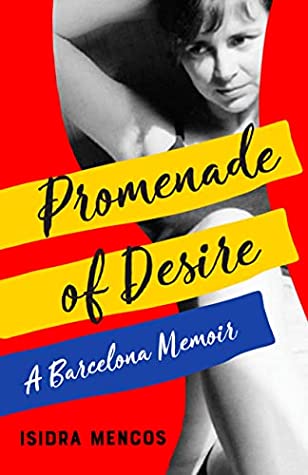

One vibrant new piece of nonfiction, “Promenade of Desire, A Barcelona Memoir” is being promoted as “a sensual coming of age story: From Catholic virgin to Mata Hari as Spain moves from dictatorship to democracy.”

All true enough, but as well as getting a grip on the massive changes in Barcelona from the 1960s until just after the Olympic games in the early 1990s, the author Isidra Mencos charts a deeply internal arc.

Apart from the apparent honesty, what I like most about this raw account of an individualist’s first few three decades is the richness of self-discovery it contains.

The author’s sexual desire is undeniable but so is her lust for experience itself.

With an equally powerful bravery, she plunges into a subculture of horny squatters, for a while, finding herself most at home with the homeless.

We also witness other improvised or adapting versions of her: as an uncertain teenager and then young adult, still racked with a punishing guilt.

Born to an affluent, emotionally-cold lawyer family (from the city’s high up Sant Gervasi-Bonanova area) who slowly fell on hard economic times, Mencos tellingly relates how her closest childhood at home was with their housekeeper/childminder/cook.

Quica, a semi-literate Andalusian woman who’d lost a husband and ten of her fourteen children during their infancy, was an anchor for the inquisitive young girl even during night-time bad dreams.

Mencos’ pure affection for this kind of person (who makes it possible for the rich to live like the rich) is touching.

It’s a clear sign that she transcended at least a snobbery of neglect. The words, ”I bawled at her death as I had not done for my lost grandparents,” poignantly ends one section in the book.

Looking at wider themes, identity is a major one. The author puts herself in the category of a “good girl,” even a “girlie girl” with “a quiet demeanor that dissolved with the ice cubes at the bottom of [her] second drink. Out came a fearless woman who declared her literary opinions with confidence and subjugated a man with a swing of her hips.”

In fact, alcohol became a major problem for her and some of the men who were her live-in lovers. Violence and abuse followed.

The details are harrowing but also somehow instructive and a kind of balance comes in the shape of a new half-American half-Japanese female friend. “A role model for me because I still lived at half speed, with a split personality,” writes Mencos.

As Barcelona remodeled and replenished itself for the 1982 Olympics, the author herself was doing something similar as a part-time translator of articles for the official games committee. Then she set a routine for passing TOEFL and SAT exams so she could do a PhD in the USA.

Ultimately, she is healed: by herself, by quality therapies, probably too by discovering a genuine, transporting passion for the “unique vocabulary and no fears, no confusion” of salsa music and dance.

Here, we see a Barcelona that would’ve even been foreign to many locals, an immigrant/latin underworld of afflicted aficionados and slaves to a beat that was new to these European shores.

One of the great qualities in this book is that we also see a person who is now unafraid of so much she had been.